We'd only been on the road a matter of days, but already it had taken its toll on the four of us. The waiting, the driving around and searching.

It was so quiet I could hear the other three breathing. No sounds in the diner but us breathing, and the old guy with the knives and fork scraping mildly against each other. At this time of night, not even other cars were stirring along the interstate.

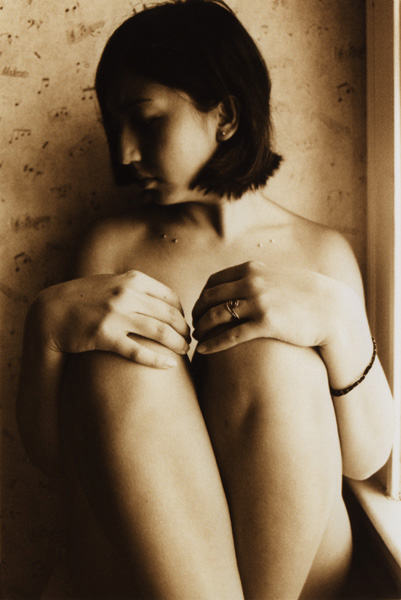

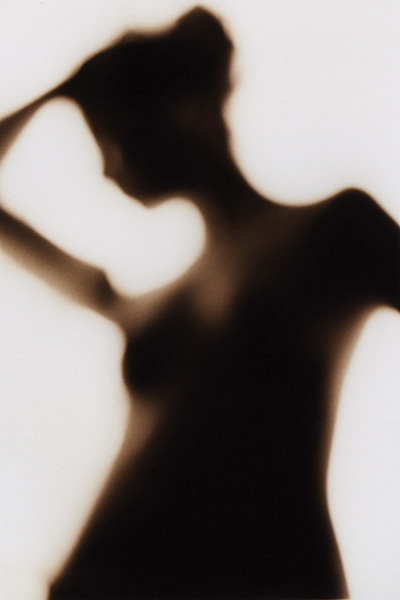

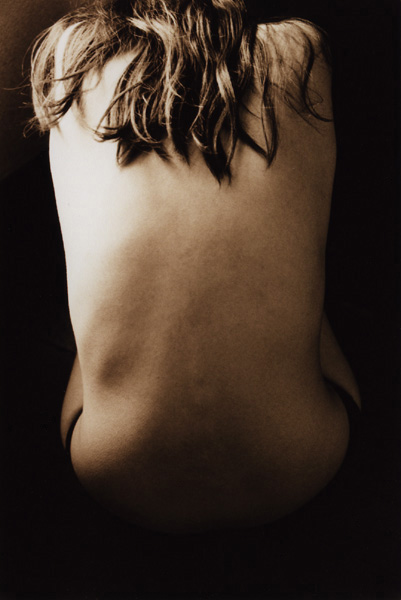

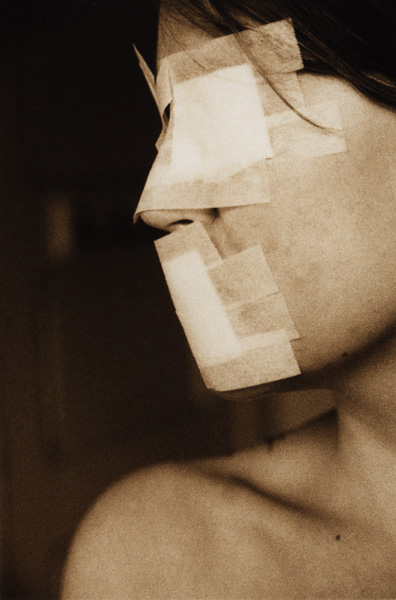

The girl looked at me and nodded to me, the nod meaning nothing really, but just looking pained. She was just newly pregnant with triplets. There were three tiny little things forming inside here, but they wouldn't be so big right now. When she stood up it was hardly noticeable underneath the layers of shirt, sweater and jacket. With her shirt off, there was only the slight hint of a swell, looking no more than if she'd just been getting a bit heavier for the winter.

We'd been to so many places on this trip that it didn't matter where we were, or why. All we wanted to know was when. One of the other two got up to make sure the restroom was private. When it was, she got up to use the restroom, like always. We watched her until the door closed behind her. The other two looked very grim. Nobody wanted to order anything, but I got a water. The waitress was an old woman with a face like clay. Pocked with dark indentations like she'd been used as an ashtray. She wouldn't let us stay if we didn't order. I said that we were tired. She said she didn't care. So I ordered a few baskets of fries to share, and a bottle of soda.

We'd been to so many places on this trip that it didn't matter where we were, or why. All we wanted to know was when. One of the other two got up to make sure the restroom was private. When it was, she got up to use the restroom, like always. We watched her until the door closed behind her. The other two looked very grim. Nobody wanted to order anything, but I got a water. The waitress was an old woman with a face like clay. Pocked with dark indentations like she'd been used as an ashtray. She wouldn't let us stay if we didn't order. I said that we were tired. She said she didn't care. So I ordered a few baskets of fries to share, and a bottle of soda.She said, “Are you all going to share that one soda, you mean?”

I ordered one more bottle. She said okay.

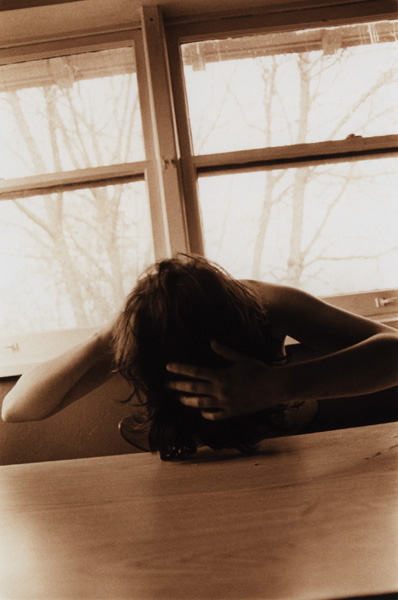

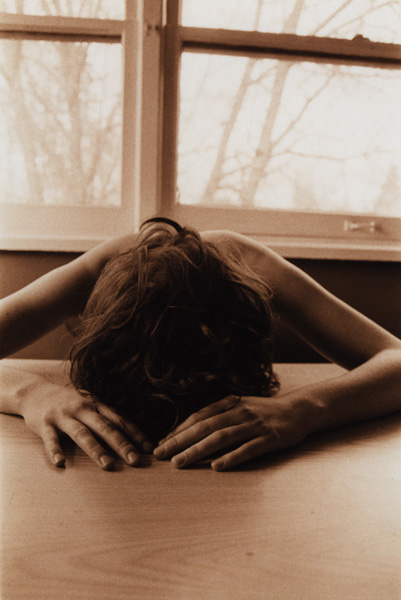

The girl came out of the restroom, her face pale and clammy. When she sat down across from me I knew that something of significance had finally happened. The other two noticed as well, but they put their heads down. The way she took a few moments to raise her head and look at me was enough. I got up and headed to the ladies room.

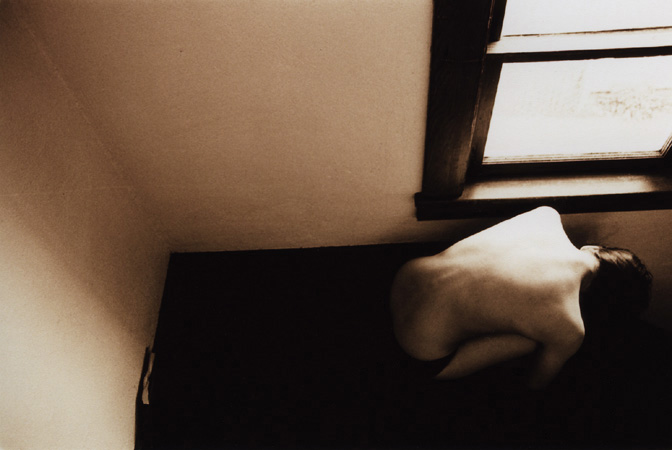

It was brighter in here, I thought. It always is in ladies rooms. The mens rooms are always, without fail, grimier than anywhere on the planet that's not a restroom, but the ladies rooms are bright and more often that not, mostly clean. I tend to feel both better about myself when I can use one of these without being hassled, and at the same time worthless. I feel worthless knowing that there's one place better in the world than out there, and it's a restroom. Private and horrible, publicly private places.

The triplets were to be put into water immediately upon emerging from the body. We tried doing it near bodies of water, like a river or a lake, but animals could sense her, and they tried to attack the creatures in her womb. The first time we got chased back to the car. The three of us learned our lesson only after the second time, when we had to beat a fox in the head with a tire iron. It had chewed up her leg a little, but nothing we had to admit her into a hospital for. This would all be over soon, and if somebody wanted to get to a hospital when that time came, then they were free to. She wanted this over with as soon as possible.

In public restaurants there would be no wild animals scenting her out, and she would be around people if the creature itself attacked. That was her reasoning, anyway, and who were we to argue? In a public restroom she could flush it if it moved, even. None of us knew what they would do. These triplets.

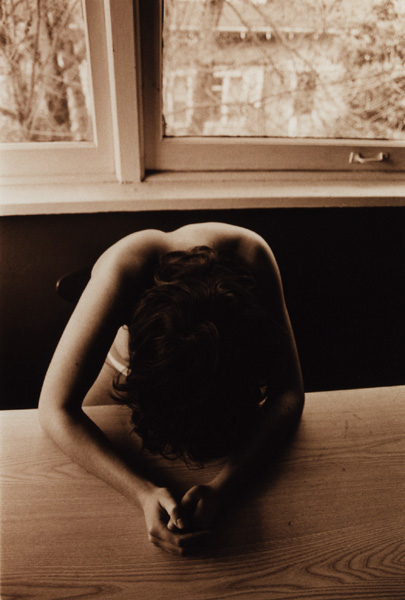

They were in her body and we had to keep her calm, so this is the way it went. City to city around the whole state in these filthy places on the side of the interstate until they were ready to be still-birthed.

There were three stalls. The one furthest from where I stood, furthest from everything else, the door was closed. But there were no legs underneath. I didn't ask if somebody was in there, I just walked in. The door swung inward.

It was cleaner in here than most of the other places we'd been.

So it was getting better in little ways as it got a little worse in others. What I saw in the clean white bowl was what I expected to see. But not how I expected it to look.

There it was, after all this waiting. All this grim time on the road, and it was finally starting. In the bowl was a child formation, dark purplish skin, bald little head. Curled up, still fetal. It did not float, but rested at the bottom of the bowl. There was nothing in there but water, and the child. I wadded up some tissue paper and covered the child so it would not startle someone into a scream if it was found after we left. I said a few things over the sleeping thing.

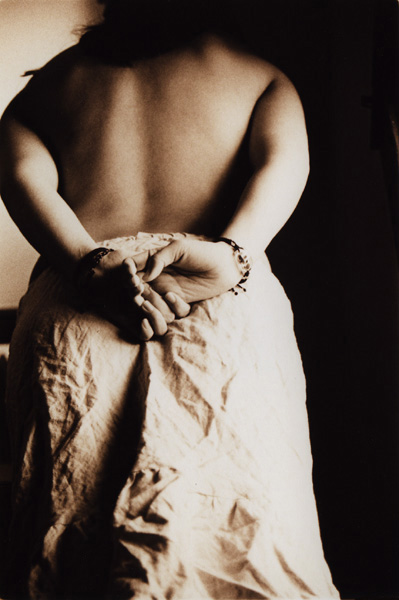

I backed up, and the girl was standing behind me, startling me for a moment. I realized I was a bundle of nerves. It was so quiet in the ladies room that I could hear her breathing over my shoulder. When I turned around, she stammered a little, then came closer, still holding her belly. She staggered a little. She looked queasy.

“Are you bleeding?” I asked.

“There was no blood,” she said. “Nothing but that.”

Pointing to the open door of the stall but not close enough to see inside of it, she stopped. “What does it look like,” she asked.

“A normal person. A fetus. Just like in pregnancy diagrams.”

She came a little closer, but stopped again, unable to look inside. “What should we do,” she asked.

“I don't know. I said the words and covered it up. I think we keep moving now. Complete the triangle.”

“Do we...”

“I don't know. Let's just leave. If we have to ask each other about it, it means none of us are capable of making the right decision unless by accident. Do you want to have any accidents?”

“No,” she said, looking downward, patting her strained stomach.

“No,” she said, looking downward, patting her strained stomach.Neither of the other two would be able to answer either. They were along for the ride because they had to be. Because we all had to be where we were, but her and I were the ones making all the decisions. I was a driver, but that's about all, as far as I was concerned. I could get us anywhere because I had a set of keys and because the roads connected to one another. That was how important I was.

We walked out of the ladies room and came up to the table as the lady waitress with the ashtray face slammed down two baskets of fries and the open pop bottles. Both bottles fizzed up and sloshed over with the force of her slamming them down on the table.

She'd watched us both come out of the ladies room together.

“You guys aren't sick, are you?” she asked us.

“No,” I said. “I think we're actually all fine now.” I looked at the other two, who had both raised their heads and were now staring at me questioningly. “Gentlemen, I guess we're on the way now.”

–

The following night, miles away, more north, in the same state but in another city, we stopped off the highway at a small, very cold little diner with only four tables and a walk-up counter. I ordered the same thing, a few baskets of fries and some pop. The other two wanted coffee so they could stay awake. I ordered them coffee.

One of the other two walked over to the ladies room and peeked inside to make sure it was private. The clerk at the counter gave him a look that was not kind.

One of the other two walked over to the ladies room and peeked inside to make sure it was private. The clerk at the counter gave him a look that was not kind.By the time I was finished ordering and sat down, it was just us three again while the girl was off in the restroom trying to miscarry a second triplet. The restroom. Our legacy is a comprehensive knowledge of ladies rooms. I sat down, sipping from one of the other guys' coffee, feeling tense in my body but pretty clear of mind. They were not shaking, but the other two were not alright. None of us were, but I think me and the girl were able to compose ourselves better than they. Like twins, they'd both stopped tucking their shirts in or combing their hair. This morning at the hotel, I noticed neither of them stopped long enough in the routines of the morning to shower or brush their teeth. I'd done all of those things. I was tired from all the driving we'd been doing, and all the searching, but I still knew to be on my toes.

If the other two were not going to last, we might have to leave them. But only afterward. We need them. If something bad happens. After it was all over, I'd be okay leaving them at some hotel in the middle of nowhere. I could put sleeping aids in their drinks and me and the girl could slip out in the night and never see either of them again. I didn't know if that would screw anything up, but I was willing to take the chance that once this was all done with, there'd be nothing left for us to really take care of. Just a bunch of pawns. A guy with a car, a girl with a womb and two sets of helping hands.

By the time I noticed it, I'd sipped the whole cup of coffee down to the end. The other guy didn't mind much. He seemed to have forgotten about the coffee. The fries came, but nobody was eating but me. The girl was taking longer than the night before. Maybe there was a problem.

I thought we were down to the last three days.

Maybe we would have to drive around more.

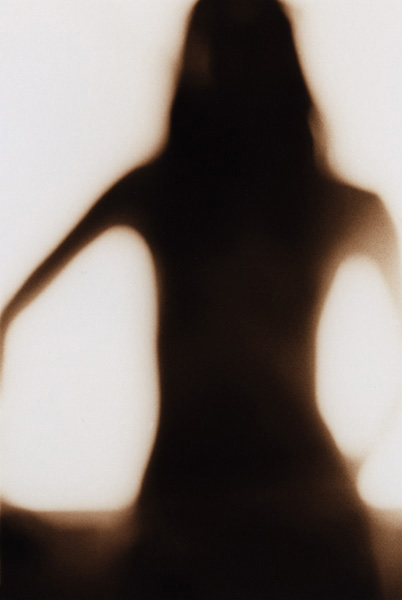

Half a basket of fries later, my mouth salty and sick from the grease and the worry and the low grade floor-scooped quality of the fries burning at my stomach, the girl came out. Her face was wet. She'd washed her face. She was holding her stomach, shaking.

Half a basket of fries later, my mouth salty and sick from the grease and the worry and the low grade floor-scooped quality of the fries burning at my stomach, the girl came out. Her face was wet. She'd washed her face. She was holding her stomach, shaking.As I did the night before, I went to the ladies room, directly to it right in front of the girl at the counter, who gave me the eye. But I didn't have time for the eye, not if the second triplet was out and we needed to be out of here quick. So I walked right into the restroom. This one was a single person room, right next to the counter. I was only in there for about ten seconds when the male cook kicks open the door.

“Find something you need in here?” the male cook asks.

I did. I found what I needed to see in the bowl behind me. So I nodded to the male cook.

He looked like he was about to hit me. “Why don't you and your friends get the fuck out of here,” he said nonchalantly.

I wiped my hands with a paper towel and threw it over the miscarried triplet, said a few things I needed to say, and we left. We left the small, still forming child behind us, purplish and stringy, curled up in the water. It was the size of a softball, this one, with kind of a hunched back. It looked sick and old. But it was new, and in the end it would be strong. When I helped the girl into the car I put my hand on her stomach. Two of the triplets were gone now, but her belly felt larger. She pulled the seat belt strap across her chest, over my hand, looking at me.

One more night, I guessed. The other two were in the back, not saying anything. They wouldn't shower or brush their teeth tonight. They wouldn't change clothes or even bring their bags into the room. I would sleep in the bed with the girl and they would sleep on the floor without blankets or pillows. They didn't care anymore. Just along for the ride now, and then when it was done, if it came to that—which it would—they would be gone, and we would never hear or see of them again.

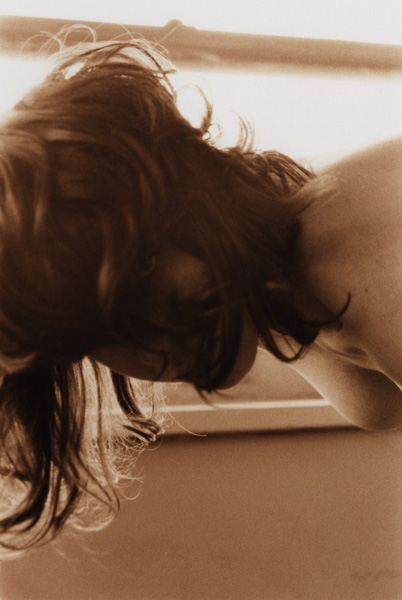

At the hotel, I put the girl in the tub and helped her wash her hair. Her arms were not strong anymore. Her whole body was weakened with the strain of the triplets. She needed rest, both mentally and physically. I ordered some food from a delivery service. They came about two hours after she'd already been put to bed. I paid for the food and left it for the morning in case anybody was hungry.

Surprisingly enough, the other two got up early and ate all of it. That made me feel a little better. It was getting too grim in the car with them saying and doing nothing. They both took showers, shaved and put on fresh clothes, like wind-up toys suddenly sprung into action. Their clothing packs had not been washed in a week, but the clothes were fresher than the past few days of what they'd been wearing. I felt better about getting into the car.

Tonight would probably be the last night.

Tonight would probably be the last night.At some diner even further north in another city—but in the same state, to make some kind of a triangle within a certain said boundary—we sat around the table in a bigger diner than the past couple of nights. This one was attached to a convenience mart and an auto station. There were lots of people everywhere. She could slip into any one of the many stalls even with people coming and going, and I could even be in there with her probably and nobody would get in our face like the last place with the security guard-ish cook.

The lady needs help, I'd say. Sorry. I have to be in here with her, you're welcome to leave until she's finished...

I bet no one would care, though. Everyone here was either hustling to get done and back on the road toward their destinations, or they were beat and shuffling around aimlessly from snack counter to magazine rack, not giving much of a shit whether the sky were raining frogs or knives.

This was perfect. Surrounded by people who didn't care about anything but themselves and their own long nights was the way to end this. Ghosts in and ghosts out.

But the girl sat in the stall for almost an hour. It became more difficult to remain unnoticed. These things need some alone time to incubate quietly, I think. No kind of fuss needs to be made, especially like last night. But last night went better than this could turn out to be if we stayed here much longer. Of course, I'm only guessing. We really don't know what's supposed to happen. We just are guessing at what will. There's just certain rules we have to follow and it'll all be done with.

Then she came out. I was waiting by the door. I'd been standing there, shifting from foot to foot for a bit before walking off to get a chair to sit in and wait. Countless women had come and gone, a lot of them stopping to glare at me. But nobody asked me questions. I was just a guy sitting in a chair outside of a ladies room.

The girl came out after what felt like half the night.

“Not here,” she said.

“Not here,” she said.I packed her into the car fast, motioned toward the other guys to follow. They didn't need me to say it twice, and we got back onto the highway. When we saw something in the distance I pointed at it and asked her, “Can we go there?”

She shrugged, then nodded.

–

It was a welcoming center, not a diner. The lights were on, but nobody was around. The doors were locked. I looked at the girl and she was sweating, leaning on the car. The other two just stood there. No help offered to the girl. I didn't blame them for not wanting to touch her. She didn't even want to touch herself, but she was in such pain she kept gripping her stomach.

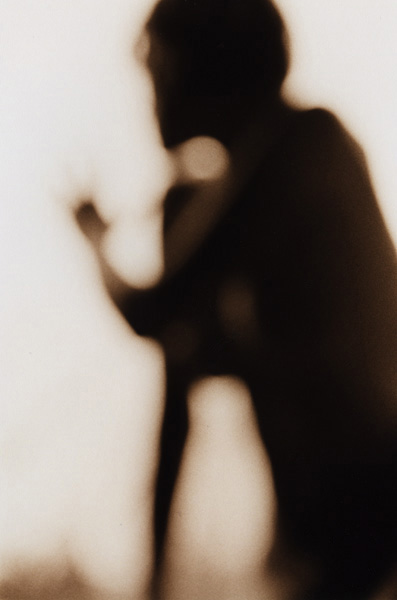

I pulled my sweater off, wrapped up my whole forearm and punched through the glass door of the welcoming center. It went right through, and nothing happened. No alarms. Barely even a ruckus. Just some broken glass, and I reached in, pulled the lock and we all walked in behind the girl, who went straight for the restroom.

I tried to punch through the candy vending machine to get some peanuts, but it wasn't so easy as the front door had been, so I picked up a heavy stapler from the front desk and smashed open the candy machine. Glass and peanuts fell out in equal measure, and I didn't really lose my appetite, but there was nothing I could do about the glass everywhere.

The girl came rushing out of the restroom.

“I didn't make it,” she said.

Great. We would have to keep doing this all night. I don't even know how much longer the other two would be holding up.

But then she filled in a better part of the void. “I didn't make it,” she repeated. “It's on the floor.”

But then she filled in a better part of the void. “I didn't make it,” she repeated. “It's on the floor.”That sounded a lot better. I went to go check on the miscarriage. Probably I could leave it here and I didn't have to check on it, but I needed to see it with my own eyes just to make sure we could really get out of here and never turn back. The other two apparently didn't feel the same way because they didn't wait for me or for her, they just ran for the door, as if on cue.

“Is it in that room?” I asked. “Are you sure!?”

“Yes,” she spat, rushing toward the smashed front door. They all hopped in the car, bleating the horn as I was still on the way to double check the restroom. They were panicked.

“No,” she pleaded from the car. “Let's just get out of here.”

But I had to see it. They would leave me if I didn't go now, but I had to be certain. If we were wrong, this would not be to our benefit to have fled so fast. If it's still inside her, in that car, and if it happens in that car, none of us will ever see the outside of that car again. I couldn't say for sure, but at the same time, I was sure of it. There could be no other outcome. It had to be in this restroom right now, and I would close the door and we would all get the fuck out of here.

I pulled open the door.

“Let's get the fuck out of here already!”

“Come on!”

“Come the fuck on!”

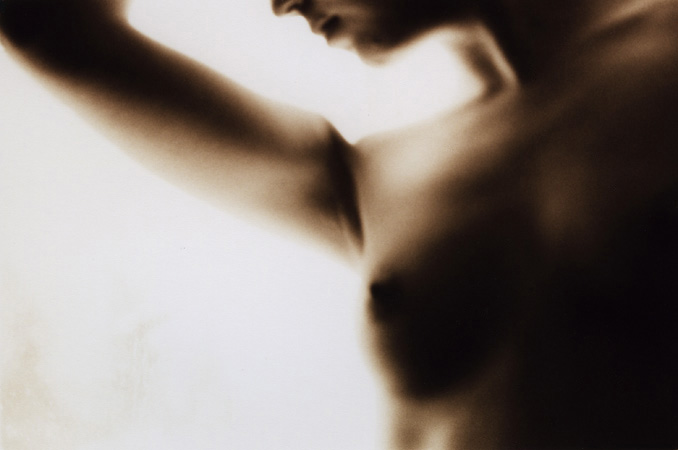

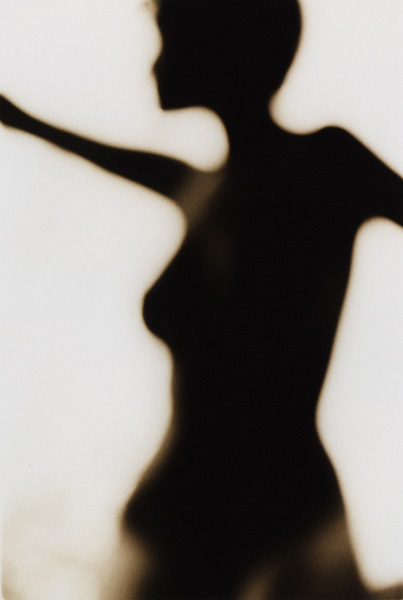

Voices from the car. All mixed up in my ears. When I opened the door it was in the middle of the room, balanced at the middle of a single tile, standing upright on its tiny, shiny little muscle-colored legs. The voices from outside lost all relevance to me. The child was standing in the middle of the floor, a trail of some thick clear fluid following behind it. It stood on both feet, facing me, its arms down.

The size of a coconut. Barely developed. Wet, slightly pulsating.

A little grayish too. In some places white kind of, or pink. If you pulled a snail from its shell and it writhed around in some kind of death throe but then stopped, it would look like this fetus of the child, somehow plucked out of its own skin. But it stood on its two feet, facing me, unfazed. Then its tiny little bulbous eyes opened, black and beady, and looked up at me.

I could never in my life describe a situation like this the way it feels. How does anyone feel in view of a miracle? You have to doubt yourself, and say to yourself, “Is this real? Am I dreaming?” Or am I scared, not processing this the right way. Of course I was scared. But I don't think I could have misrepresented this. I'd already seen the first two. That was clearly enough time to get over it. What does somebody do when faced with a miracle? I can't run. I should, but my body wasn't letting me. What if the things people call demons are just part of nature? Nature can be hideous too. It's not that hard. I had every right to stand here in awe. This thing had made some kind of pilgrimage. From spoken words in a basement, to the womb, through the birth canal, into this welcoming center. What better place?

I said the words. But I said them nicer, somehow, like I was trying to be nice about it.

It took a tiny step forward, seemingly to keep its balance. It didn't blink. Just stared up at me. In its eyes I could see nothing. Just blackness. This child was so much smarter than me, I could tell right off the bat. Even nature can be miraculous, look at the human circulatory system. This thing had purpose. Something I fully could not comprehend, and for that I was glad.

Only I'd had some kind of job to perform. And look. I did it, I was part of something big.

The triangle was complete. We'd done it the right way.

It took another step closer to me. This step seemed more deliberate.

Very quietly, I closed the restroom door, and I took two steps backward, still facing the door in awe. Miracles were happening there, and I had been part of it. Mother nature or whatever, it just gave birth again. New ideas popped into my head. I could comprehend none of them. Time to leave the triangle. Expecting to see the handle on the door moving, I kept my face toward the door, stepping carefully backward so as not to trip over myself. I don't even know if I could still hear the car horn outside. Maybe they'd given up and left. In fear. Fine by me.

I just kept my eyes on the door, fearfully too. Ridiculous. The thing wasn't even tall enough to reach my knees. It couldn't get to the handle of the door. But maybe I wasn't fearful of that, in particular. I had no clue what I was supposed to be scared of, or what was coming. But it was coming through that door, and it would get out. That's why we'd done all this. So they could get out.

I wondered what it would look like when it happened. How it would get out. This triplet.

Maybe it could do anything.

Yours,

JARET.

5:30pm / Christmas day.