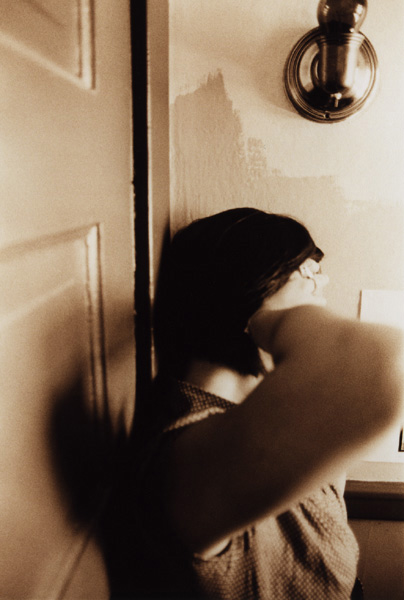

My arm didn’t fit so well into the sink because the basin was small and cramped, so even bunched up and standing on a stool, it was giving me cramps to hold myself in that position to let the water run over the cut in my skin. It would have been a lot easier to do this in the bathtub, but the tub was broken and the water which poured from the nozzle was pinkish in color and I wouldn’t want that anywhere near an open wound.

If I didn’t get cleaned up soon, I’d get found out and I’d have to explain away something that didn’t happen in the better interest of avoiding talking about what really happened, which would land me in a pretty bad situation, especially in that it could get us in trouble with the landlord again and they might kick us out for good instead of just threatening it.

Someone would be asking questions regardless of how well I avoided the subject, but I just needed to get cleaned up and I hoped I didn’t bleed everywhere in the apartment across the hall. It was the first time I had tried climbing in through the window, and in my haste I cracked my elbow pretty good and sliced my arm open recoiling from it and then fell headlong through the kitchen window and into the bushes outside, one floor down.

My pants were fucked up, my ankle twisted and my arm looked like it might need stitches. The pants could be thrown out and no one would notice. My ankle would get better. But the cut looked bad. I was so scared that I could just barely register the actual pain of it, but I know it looked bad. It wasn’t bleeding too much, though. It was hard to look at it.

If I needed stitches there would be nothing that I could do about this, they would find out, and I would place all of my allowance on it that we would be kicked out of the apartment.

The next morning when I passed by Mrs. Jakob’s door, I could hear them talking inside, her and Mr. Jakob. I heard the word ‘police’ and I ran to school. I think they thought it was a burglar. By the time school was out, their broken kitchen window was replaced, and it was quiet in the complex.

In my bed, I stared at the stains on the ceiling. The apartment above ours had probably been leaking since before I was born. Any day now, some part of the apartment above might fall into mine, right through that ceiling. It might even happen while I slept in my bed, in the night, and I’d never know it happened; the ceiling would finally give way, and the softened plaster and beams or whatever would fail underneath the weight of whatever was in the room above and it would come crashing down and crush me and kill me.

I stared at the stains and thought of Mrs. Jakob.

During the day she cries sometimes, when her husband is out at work. I slid in through the kitchen window to watch her this time, and she had no idea I was there until the little alarm went off on my wristwatch and I panicked and ran. Mrs. Jakob probably didn’t hear my watch go off, because she was in the next room and because the sound of the little alarm was so faint it couldn’t possibly work to wake anyone up from sleep. It was probably better suited as a reminder to a fully-awake person, like if they had something in the oven and were reading a book while dinner was baking.

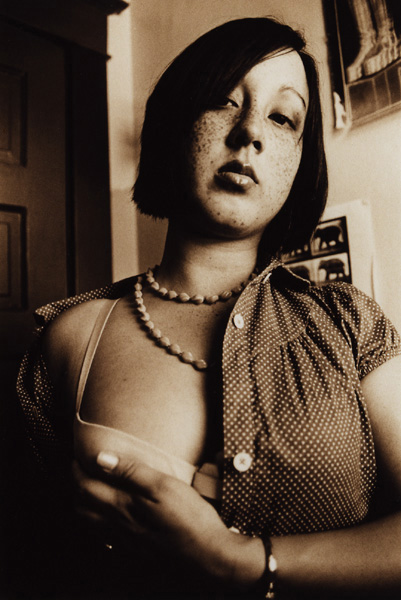

My arm throbbed and I could barely move it all day, so I held a plastic shopping bag partly filled with ice against it. And just stared at the ceiling, thinking of Mrs. Jakob. She looked really sad to me all the time. Sometimes she winked at me, slowly, smiling a little, like she had some shameful secret and I was supposed to know what it was, or that I did know what it was. It made me feel a little shady, that strange look, and a little afraid, but also a little neat too, in some way I couldn’t know. I certainly wouldn’t mind knowing a secret with her, but I didn’t know one. She just winked at me and every time she did that I grew red in the face.

Part of me knew that I liked her, but the other part of me—the one that always made more sense out of things—would just laugh inside my head and tell me what an idiot I was being. I thought sometimes that maybe she winked at me because she liked me too. But I was in the third grade, that other part of me would say, antagonizing and shrill.

I liked to look at Mrs. Jakob whenever I could. And I did too, through her kitchen window sometimes after school, when she was sitting in the small dining room, crying very softly to herself. It was only just that one time that I went any further and crawled into the house to watch her cry.

Out in the hall, the large gray hound that belonged to another neighbor slinked past me, nosing at Mrs. Jakob’s door, and then it turned around and eyed me suspiciously. I had lately grown very nervous about the dog, and thought that maybe it knew I had broke into Mrs. Jakob’s house and that it knew I was the one who broke the window. We’d get kicked out of the apartment complex if the dog told anyone. I already broke the dryer in the basement and got caught, and I spilled bleach all over another neighbor’s television set during an Easter Egg hunt and the television blinked out and killed the power in the complex for one whole night. My parents had been so embarrassed that we hadn’t been invited to the next party that they have only just barely spoken to me since.

The gray dog sniffed at Mrs. Jakob’s door and eyed me again.

If the dog really knew what I had done then I had to get rid of the dog.

I called this kid Menden over from down the street and offered him five dollars to kill the dog. He said he would do it, though I kind of feared he’d just steal my money. But I had no choice. I gave him the money at school so the dog wouldn’t know it happened, and I told him to come over on a Sunday morning before noon when most of the people in the complex were either sleeping or at church, and I watched out from a crack in the blinds as the kid snuck into the hallway and then, a couple minutes later, snuck back out. At school he told me he hadn’t seen the dog anywhere but I told him that dog isn’t allowed inside the apartments so he’s always roaming the halls if he’s not sleeping in the sunny spots of the fenced-in yard. So Menden came back the next Sunday—at a loss of three more dollars on my part—and since that Sunday morning no one has seen the gray dog anywhere. There are badly-lit pictures of him on half-assed but seemingly earnest photocopied sheets of paper over a telephone number to call if anyone sees him, and these sheets are stapled to telephone poles across the next two streets over. I also gave Menden my lunch at school if he promised not to tell me what he did with the dog or if the dog knew that I had paid for its death.

“It is dead, right, Menden?”

“I thought you didn’t want to know, smartass,” he says to me, eating my lunch.

“That’s right. Forget it, I don’t want to know. The dog’s not coming back, though, seriously?”

The kid looked at me and smiled and told me it might be worth my money just to make sure, and so two weeks later when I could save up another five dollars I gave that to him too.

Within that time my arm got infected and I had to go to the hospital and my father told me that he was going to kill me if I didn’t shape up, and I figured that meant he might send me away to live in a boy’s home, which is how he threatened me every here and there when I acted up or broke something or got caught trying to break something. This time he didn’t even ask me how it happened. He just told me I was in for it if I didn’t wise up. The doctor asked him how I did it, though, and my father said, “Who the fuck knows? The kid’s a goddamned idiot.” I got really scared for a second that they would think my father had done it to me, and the grief that would cause could get us kicked out of the apartment complex for sure; if they thought for a second that my father was beating me up they’d kick him and us out. The doctor told my father to calm down and after they left the room and talked where I couldn’t hear them, I tried to come up with an excuse. My arm wasn’t just cut, it was sliced open. And infected. I couldn’t move my arm so well or the shoulder either. I pictured myself with one arm, like if they had to cut it off. But they only had to clean it and gives me stitches, and I said I broke a window, but didn’t finish with the where or how, and my father squinted his eyes at me and I could see his face getting red, and I knew he wouldn’t hit me, but I also knew that he didn’t like me. And that this was going to get a lot worse at home, and that nobody would ask me what window, or where, because they knew already.

But no one ever said anything. About the window, my arm . . . or anything else.

Mrs. Jakob was sitting down in the basement one afternoon, reading a magazine while waiting for laundry to dry. The new dryer was faster than the old one, which I had broke one day playing inside of it. Somehow I broke it for good and it wouldn’t spin. The landlord told my parents I wasn’t allowed down there anymore. But I went down because I had followed Mrs. Jakob down there, and when I walked in, she winked at me, and I could swear she thought I knew about some kind of secret that she did.

I watched her patiently, for about half an hour, while she sat in a small plastic chair and read from the magazine, turning the pages leisurely, looking up at me every couple of minutes or so, but she didn’t say anything to me, and I didn’t say anything back.

Yours,

JARET.

No comments:

Post a Comment