3:20am.

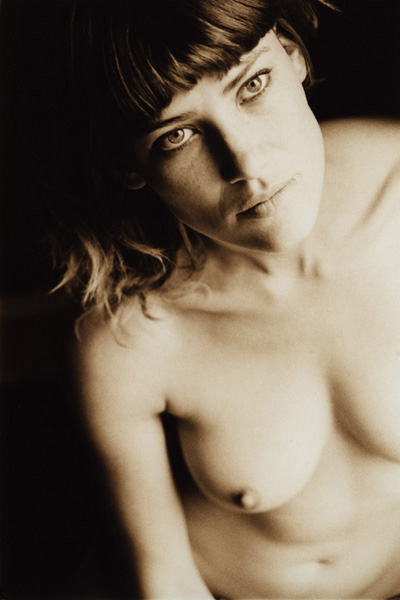

Perfume was all I could think of, with roses and lilies.

The way she looked when our grandfather was here after his stroke, when we milled around by the soda machine in the waiting room for half the day, thumbing through childrens books and newspapers.

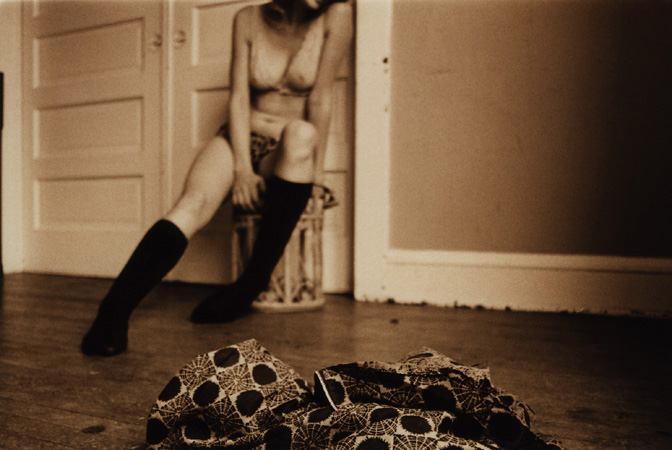

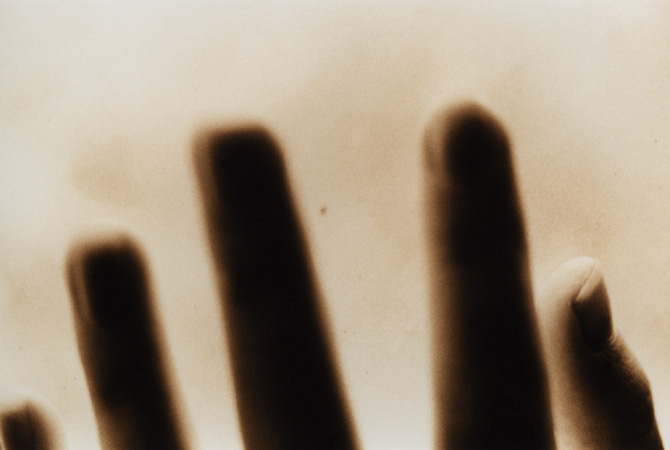

I could still smell the perfume on her, mixing with the stale air and the chemicals on the walls and floor. That dark orange dress with the white flowers sewn into the hem. Running faster than me. Beating me to the whatever it was -- the

everything, of anything there ever was. A part of me loved that, but the real version of me that I believed in detested that I had been such a simple fool.

The shock was still working against the hard parts of my muscle and my body just wouldn't work right, tensing up at the most inconvenient of turns, but I carried all my stuff and shuffled past the reception desk at the front entrance of the floor and made a perfectly respectable exit from the hall, down the elevator and into the lobby. To either side of me in the vast room at the bottom of the building there shone the possibility of a different life, spilling in from the glass doors, waiting for me outside. In here was a death hall, and all of these guests only haunted the lobby ahead of the ghosts waiting in line upstairs, filling the building. The doors shone brighter. Tellingly, but almost fantastical anyway, because of the floor to ceiling glass, it was angelically bright with the sun, and glowing as a healing wound to the stifled murky air of the lobby. I could sense the very

importance of it, staring at the doors and how close I was to getting out. A tinkling of bells sounded in my head, tiny and wintry like chimes over the threshold of a door, leading me outside regardless of what was waiting for me.

The skin on my arms and belly crawled underneath the suit. I pulled at the knot in my tie, slow and curious and unable to get a hold of myself, and I undid the top button. All while walking briskly out of the building at an embarrassing, awkward pace, sighing, carrying a box of clothes and a few manila files with hospital reports that looked more like selfishly assumed pencil sketches of people who had survived car accidents but wouldn't ever be considered truly human anymore.

They were blueprints for my sister's new body.

What was waiting for me outside was uneventful -- a hot, muggy afternoon, laced with distant chatter and the sounds of cars circling in the crowded lot. I felt drab and cheated. Nothing interested me and I felt free. What a cheat. What did I escape?

Objectively, I was unaware of most everything in my life. The hospital somehow exemplified some kind of possessive, insistent pull at me that had always seemed to reel itself before my eyes but never formed into something I could grasp. The hospital itself felt like it had always been there in my heart, sitting over the hill like that, sucking up nutrients from the ground as it grew more ancient and total. It had been there my whole life, changing shape as the years shifted around, showing itself now in the form of the building. If I'd been unaware before, I was now seeing things more clearly. Before the doctor could even really make me understand what had happened to my little sister, I'd torn loose from the room as if I'd just been let out of an unjust jail sentence, and though I did not seek safety or being free as I ran, I was nonetheless searching for

something.

In the parking lot, behind the wheel of my car, I gazed out over the hot steam rising from the hoods of the long line of vehicles that led up to the hospital.

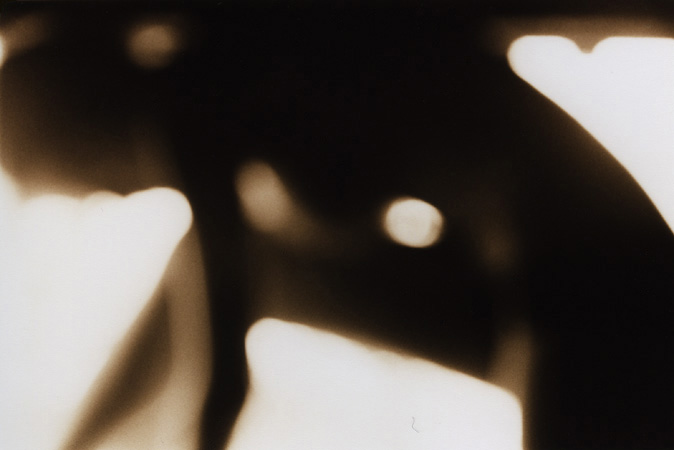

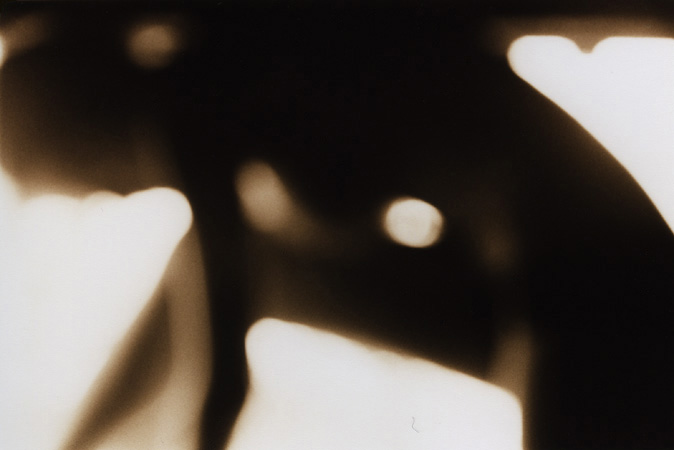

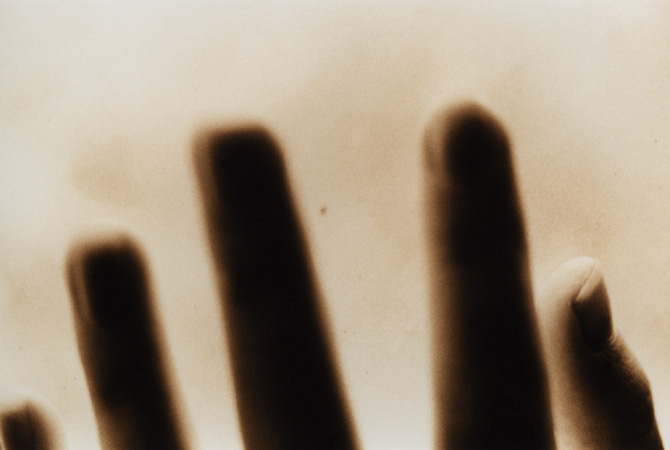

Structurally, it loomed above, high up into the dome of the city sky. The windows were mostly white with drawn curtains, pierced here and there by black dots with opened windows that looked inward like unhealthy pores in the dirty concrete body. My sister was in there, behind one of those white spots. The nurses would have their hands on her by now and the doctors would have their hands sticking into her. Her skin would smell sour and her hair would be brittle and sweaty. She wouldn't have that pretty smile, and her body would be separating under the knives that would make her fit for life only in a wheelchair.

Somewhere there in the building was a doctor in mid-sentence, whom I'd escaped before he could do this to me. Whatever it was his words had meant, I'd escaped it fair and square. Shrugging his shoulders, he would now be watching my sister in her lapsed sleep. In the building, in one of those rooms, her insides were being pressed and pulled. The legs she used to run with -- and which would beat me to wherever we used to be going -- were on a metal table away from the bed.

Yours,

JARET.